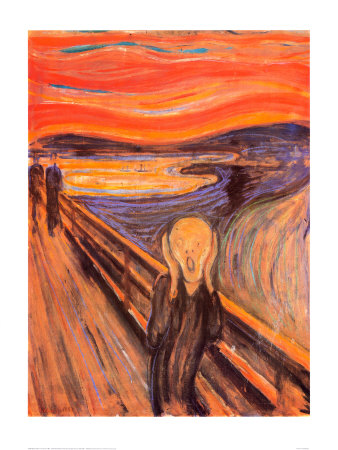

Okay. No more brave assertions about “our thoughts and prayers being with the victims.” No more gibberish from television commentators about “tragedy bringing us together.” (The day someone comes to me with that line when my child’s life is taken in this way, is the day I will get a gun.).

It is time to get furious. This latest shooting “episode” is repulsive. Actually, in a healthy country and culture there would be rioting in the streets. Twenty years ago William Bennett wrote a book entitled, “Outrage,” claiming that Americans had lost the capacity to be morally furious. His fury was directed at….Bill Clinton’s sex life. I wonder if we will hear from Mr. Bennett today, or from anyone on the right, where they wear their patriotism on their shirtsleeve. Because it might occur to them that this ought to be profoundly humiliating to anyone who boasts (as I do) that America is the finest country on the earth.

There will be no more fence-straddling by me on the issue of gun control. I had been inclined to give up on this one—too many decent people, including friends, are gun owners. And there are so many other things to be furious about. And, well, the second amendment says what it says. Or does it? There has been a long-running debate about whether the amendment protects the individual’s right to own a gun, or the right of states to operate a militia.

But really who can stand on legal niceties in the face of this? Read this excerpt from a fine piece of exactly the kind of outrage that ought to be universal, by the author Adam Gopnik, writing in the New Yorker today.

After the mass gun murders at Virginia Tech, I wrote about the unfathomable image of cell phones ringing in the pockets of the dead kids, and of the parents trying desperately to reach them. And I said (as did many others), This will go on, if no one stops it, in this manner and to this degree in this country alone—alone among all the industrialized, wealthy, and so-called civilized countries in the world. There would be another, for certain.

Then there were—many more, in fact—and when the latest and worst one happened, in Aurora, I (and many others) said, this time in a tone of despair, that nothing had changed. And I (and many others) predicted that it would happen again, soon. And that once again, the same twisted voices would say, Oh, this had nothing to do with gun laws or the misuse of the Second Amendment or anything except some singular madman, of whom America for some reason seems to have a particularly dense sample.

And now it has happened again, bang, like clockwork, one might say: Twenty dead children—babies, really—in a kindergarten in a prosperous town in Connecticut. And a mother screaming. And twenty families told that their grade-schooler had died. After the Aurora killings, I did a few debates with advocates for the child-killing lobby—sorry, the gun lobby—and, without exception and with a mad vehemence, they told the same old lies: it doesn’t happen here more often than elsewhere (yes, it does); more people are protected by guns than killed by them (no, they aren’t—that’s a flat-out fabrication); guns don’t kill people, people do; and all the other perverted lies that people who can only be called knowing accessories to murder continue to repeat…

Read the full article here http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/newsdesk/2012/12/newtown-and-the-madness-of-guns.html. And I would urge you also to read his previous columns, after the shooting in Aurora this year http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/newsdesk/2012/07/aurora-movie-shooting-one-more-massacre.html, and the episode at Virginia Tech http://www.newyorker.com/talk/comment/2007/04/30/070430taco_talk_gopnik#ixzz2F5UTvu6.

"Since he was capable of observing, he grew fond of observing in silence. ... And if it was necessary to focus the gaze and remain on the lookout for hours and days, even for years, well there was no finer thing that this to do." -- Amos Oz, "To Know a Woman"

Friday, December 14, 2012

Sunday, December 9, 2012

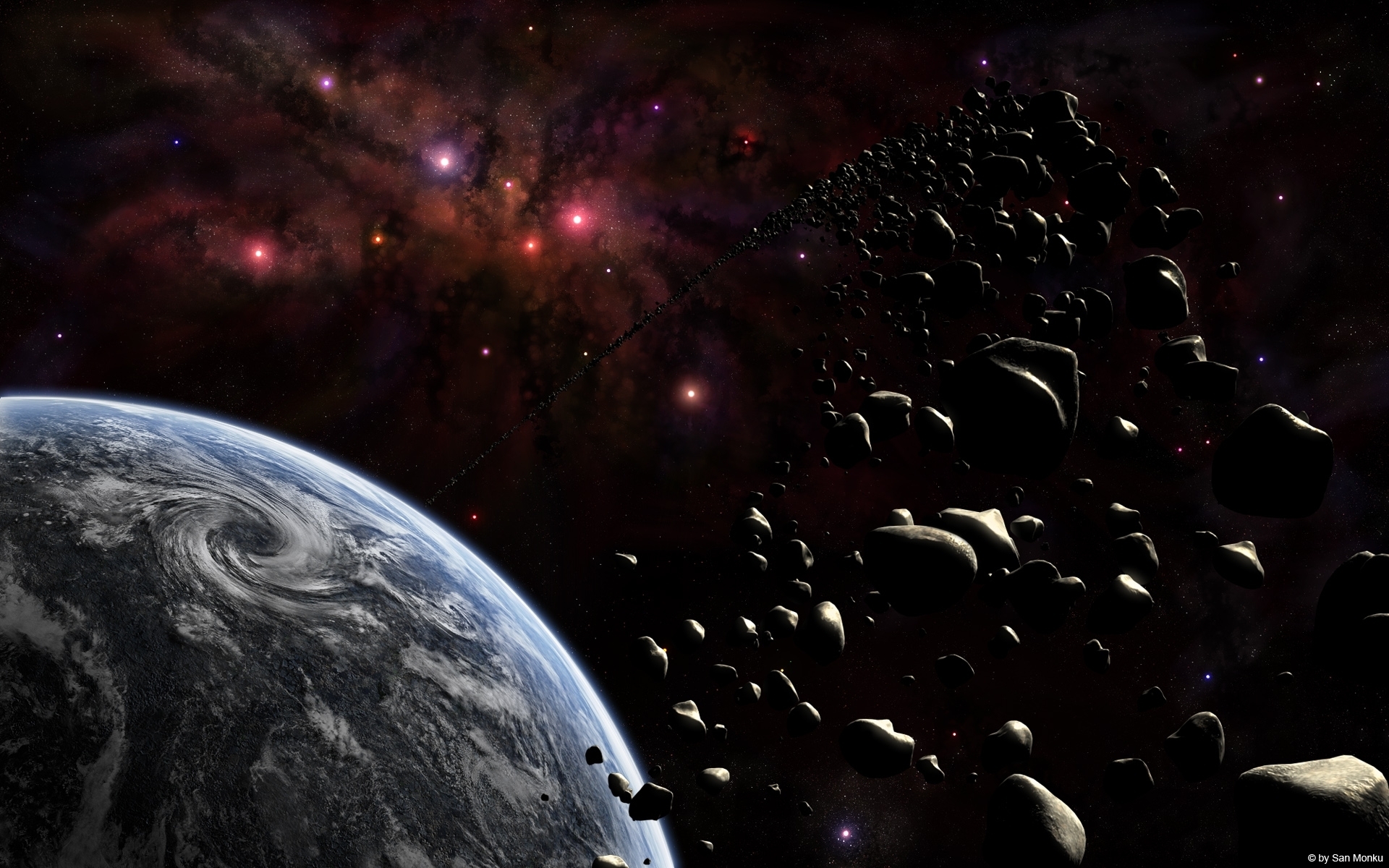

Skyfall: Worrying About the End

“This is the end,” Adele sings in the lush title song to the latest Bond movie, “Skyfall.” Apocalyptic thinking infects even our popular entertainments. And no wonder…Hurricane Sandy may have caused even global warming atheists and agnostics (I have had my doubts myself) to acknowledge at last that nature is taking its revenge on us, that flooded eastern seaboard cities may be our future. Terrorism haunts us still from the shadows. The bottom has fallen out of Syria and (as I write this) there is a real fear that Assad will use chemical weapons on his own people. The latest round of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has only just played itself out in Gaza (and no one even pretends to think there won’t be another round). Behind the Kubuki theater of threats and counter-threats, diplomacy and crippling sanctions, lay the real possibility of a military strike by Israel (with or without the overt or covert cooperation of the U.S.) on Iran, almost certainly igniting a regional or global war. And “fiscal cliff” is now on everyone’s lips as a reminder--far, far, far, too late--that what we call "our way of life" is not a given.

“This is the end,” Adele sings in the lush title song to the latest Bond movie, “Skyfall.” Apocalyptic thinking infects even our popular entertainments. And no wonder…Hurricane Sandy may have caused even global warming atheists and agnostics (I have had my doubts myself) to acknowledge at last that nature is taking its revenge on us, that flooded eastern seaboard cities may be our future. Terrorism haunts us still from the shadows. The bottom has fallen out of Syria and (as I write this) there is a real fear that Assad will use chemical weapons on his own people. The latest round of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has only just played itself out in Gaza (and no one even pretends to think there won’t be another round). Behind the Kubuki theater of threats and counter-threats, diplomacy and crippling sanctions, lay the real possibility of a military strike by Israel (with or without the overt or covert cooperation of the U.S.) on Iran, almost certainly igniting a regional or global war. And “fiscal cliff” is now on everyone’s lips as a reminder--far, far, far, too late--that what we call "our way of life" is not a given.

"Skyfall," the movie, worries too about the end—the end of the usefulness of human intelligence in the face of those enemies in the shadows who wreck havoc through cyberspace. Worries about the end of the usefulness of the double-0 agents, and of Bond himself, (played again by Daniel Craig, and looking in "Skyfall" as if the miles have begun to take their toll). And in a bit of self-referential mockery it worries about the usefulness against such an enemy of all those gadgets and devices that Bond has used for 50 years to dodge death and surprise his enemies. (“What did you think you were getting, an exploding pen? We don’t really go in for that kind of thing anymore.”) And the end really does come to “M” in a shootout at Bond’s childhood home in Scotland, an affecting scene (and for the sake of the series a sad one, since it seems that any movie with Judy Dench in it can never be a really bad one.) It’s also a bit disappointing to this movie-goer that the villain wreaking worldwide havoc with cyberspacial ease is not a politically or religiously motivated visionary with a global agenda, but a demented sociopath with a personal one. But that too may be true, in its way, to our apocalyptic fears: all of human history may be at the mercy of such types.

Well, this is a Bond flick and people come to the theater to get away from politics. And so of course Bond and his devices do emerge victorious (he’s even equipped with a 60s vintage hotrod with headlights that fire bullets). The series promises to go on satisfying audiences, with Ralph Fiennes newly incarnated as M. And then there is that theme song by Adele, which is its own reward. Tuesday, September 11, 2012

In Memory: "The Unmentionable Odor of Death"

(This haunting and grave poem, wrtitten by Auden about the invasion of Poland by the Nazis and considered by some to be the greatest poem of the 20th century, made the rounds--on the streets of New York and later by email--in the days immediately following the attacks eleven years ago.)

September 1, 1939

by W.H. Auden

Accurate scholarship can

Into this neutral air

And the international wrong.

The lights must never go out

The music must always play.

All the conventions conspire

To make this fort assume

The furniture of home;

Lest we should see where we are

Lost in a haunted wood,

Children afraid of the night

Who have never been happy or good.

Is not so crude as our wish:

What mad Nijinski wrote

About Diaghilev

Is true of the normal heart;

For the error bred in the bone

Of each woman and each man

Craves what it cannot have

Not universal love

But to be loved alone.

From the conservative dark

Into the ethical life

The dense commuters come

Repeating their morning vow:

“I will be true to the wife,

I’ll concentrate more on my work.”

And helpless governors wake

To resume their compulsory game:

Who can release them now?

Who can reach the dead?

Who can speak for the dumb?

All I have is a voice

To unfold the folded lie,

The romantic lie in the brain

Of the sensual man in the street

And the lie of Authority

Whose buildings grope the sky:

There is no such thing as the State

And no one exists alone;

Hunger allows no choice

To the citizen or the police

We must love one another or die.

Defenceless under the night

September 1, 1939

by W.H. Auden

I sit in one of the dives

On Fifty-second street

As the clever hopes expire

Of a low, dishonest decade.

Waves of anger and fear

Circulate over the bright and darkened

Lands of the earth

Obsessing our private lives;

The unmentionable odor of death

Offends the September night.

Unearth the whole offence

From Luther until now

That has driven a culture mad,

Find what occurred at Linz,

What huge imago

Made a psychopathic god:

I and the public know

What all schoolchildren learn,

Those to whom evil is done

Do evil in return.

Exiled Thucydides knew

All that a speech can say

About democracy,

And what dictators do,

The elderly rubbish they talk

To an apathetic grave;

Analyzed all in his book,

The enlightenment driven away,

The habit-forming pain

Mismanagement and grief:

We must suffer them all again.

Where blind skyscrapers use,

Their full height to proclaim

The strength of Collective Man

Each language pours its vain

Competitive excuse:

But who can live for long

In an euphoric dream;

Out of the mirror they stare,

Imperialism’s faceAnd the international wrong.

Faces along the bar

Cling to their average dayThe lights must never go out

The music must always play.

All the conventions conspire

To make this fort assume

The furniture of home;

Lest we should see where we are

Lost in a haunted wood,

Children afraid of the night

Who have never been happy or good.

The windiest militant trash

Important Persons shoutIs not so crude as our wish:

What mad Nijinski wrote

About Diaghilev

Is true of the normal heart;

For the error bred in the bone

Of each woman and each man

Craves what it cannot have

Not universal love

But to be loved alone.

From the conservative dark

Into the ethical life

The dense commuters come

Repeating their morning vow:

“I will be true to the wife,

I’ll concentrate more on my work.”

And helpless governors wake

To resume their compulsory game:

Who can release them now?

Who can reach the dead?

Who can speak for the dumb?

All I have is a voice

To unfold the folded lie,

The romantic lie in the brain

Of the sensual man in the street

And the lie of Authority

Whose buildings grope the sky:

There is no such thing as the State

And no one exists alone;

Hunger allows no choice

To the citizen or the police

We must love one another or die.

Defenceless under the night

Our world in stupor lies;

Yet dotted everywhere

Ironic points of light

Flash out wherever the Just

Exchange their messages:

May I, composed like them

Of Eros and of dust,

Beleaguered by the same

Negation and despair

Show an affirming flame.

Tuesday, August 21, 2012

Scenes From an Expiring Season of Decline

For several years now I have fancied that I could feel the tipping of the earth from summer into fall, some subtle change in the air even in the midst of an August heat wave. A middle-age guy’s fancy, maybe, reflecting the sense of his own declining. Or perhaps it is just the sublimated awareness of the routine signals of summer’s end—back-to-school sales and the like. After twelve years in these parts, I have come to love the fall—September through Christmas is my favorite time of year. On a recent morning at the lake with my dog, I could feel autumn approaching, even as the summer sun still beat on the rocks of the breakwater. And this is the year I officially declared that I no longer like summer. It might have been the July heat wave, during which on two separate occasions the power went out, but I think I am done with summer on general principles. Summer is not a season to be solitary—all those sun-scorched days make you feel over-exposed, and it’s a young person’s season anyway. In case you haven’t already guessed, I am not feeling young.

For several years now I have fancied that I could feel the tipping of the earth from summer into fall, some subtle change in the air even in the midst of an August heat wave. A middle-age guy’s fancy, maybe, reflecting the sense of his own declining. Or perhaps it is just the sublimated awareness of the routine signals of summer’s end—back-to-school sales and the like. After twelve years in these parts, I have come to love the fall—September through Christmas is my favorite time of year. On a recent morning at the lake with my dog, I could feel autumn approaching, even as the summer sun still beat on the rocks of the breakwater. And this is the year I officially declared that I no longer like summer. It might have been the July heat wave, during which on two separate occasions the power went out, but I think I am done with summer on general principles. Summer is not a season to be solitary—all those sun-scorched days make you feel over-exposed, and it’s a young person’s season anyway. In case you haven’t already guessed, I am not feeling young.*********************

I lost a great friend this summer. After outliving by a couple of years her doctors’ predictions, she succumbed at last in her late seventies to pulmonary fibrosis. The last year-and-a-half or so of her life she had a steady stream of visitors--friends, sons and daughters and grandchildren, paid and un-paid help. I would periodically buy lunch from Alladin’s and take it to her apartment, sit with her and talk. I feel fortunate for that time I had with this great lady, though I could have done more. At her memorial service, in a sweltering Methodist church, those of us who had been her regular visitors all agreed we’d gotten the better part of the bargain. The last time I went to visit her, about a month-and-a-half before her death, she was in a far better mood than I was though it was fairly certain she wouldn’t see the end of the year—a fact that she laughingly referred to as her “transitioning.” One of her best friends spoke at the service of how her gracious and cheerful acceptance of the help she needed allowed the community that gathered around her in her last year—bringing lunch, helping to clean the apartment, giving her backrubs, or just showing up to talk or watch a movie or a favorite television show—a glimpse of a true Christian community. Maybe. Flannery O’Connor wrote something to the effect that you spend your whole life learning how to die, and if that’s true our great friend must have lived well.

**************

"Everything will be alright in the end. If it’s not alright, it must not be the end.” That’s the motto, or signature if you will, to the summer movie, “The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel,” and it suggests, when you carry its implications to their logical conclusion, a fairly optimistic view of death. This makes sense, because for modern types, as for the seven aging Brits who decide to outsource their elderly years to an “exotic” hotel for “the elderly and beautiful,” death is not the problem. The problem is growing old.

"Everything will be alright in the end. If it’s not alright, it must not be the end.” That’s the motto, or signature if you will, to the summer movie, “The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel,” and it suggests, when you carry its implications to their logical conclusion, a fairly optimistic view of death. This makes sense, because for modern types, as for the seven aging Brits who decide to outsource their elderly years to an “exotic” hotel for “the elderly and beautiful,” death is not the problem. The problem is growing old. How to do it? (The new buzz-phrase about “sixty being the new fifty” or “fifty being the new forty”, by the way, strikes me as very bad business, the wrong way to do it. Much better, it seems to me, to face the music and just admit it—you are growing old.) “The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel” is a sweet and thoughtful and occasionally funny movie that is about twenty minutes too long, has possibly one too many characters and one too many sub-plots, and suffers from an ending that is entirely too perfect. There are very fine acting performances by (of course) Judy Dench, Tom Wilkinson, and Bill Nighy. Dev Patel, of “Slumdog Millionaire” fame, is Sonny, the handsome and endearingly inept manager of the hotel, once grand but now dilapidated.

Guest: “My room doesn’t have a door! I won’t stay in a room without a door!”

Sonny: “You can have my room.”

Guest: “But does it have a door?”

Sonny: “Yes, a most effective one.”

The stories of the seven guests—including an especially well-wrought story of reunion, after decades apart, between Graham Dasherwood (“I’m gay, but these days mainly in theory”), and a now elderly Indian gent with whom he had been in love as a younger man—revolve around the quest for love or companionship as a buffer against aging.

Or is it the quest for sex? Norman is an aging playboy, whose good looks have left him and who arrives at the hotel looking mainly to get laid. I’d ax him from the script, but I suppose he serves as a useful counter-point: after scoring with a life-long English resident of India, he relates his experience, which he describes as “the mountain-top,” with Graham who has spent the entire night talking with his long-lost love.

I suppose there are people whose mountain-top experiences have been exclusively, or primarily sexual ones. Alas, I can’t claim to be one of them, although I freely admit that this may only indicate that I’ve been doing it wrong. (On the other hand, it was another fifty-year old friend of mine, with the experience to back up his words, who said that “sex is over-rated.”). The birth of my daughter, many countless experiences watching her grow up, a trip I took by myself across the country in my twenties, some subsequent travel as an adult to Europe and the middle East, some memorable instances of watching really inspired performers, musicians, and athletes doing what they do and doing it excellently—these are what I remember as the mountain-top. But who knows what will count in the end? “Life is lived forward but understood backward,” according to Kierkegaard, so it may be that what I will realize as crucial when my own flame is about to go out, was lunch from Alladin’s with an elderly dying lady.

Sex and love and companionship. Such are the preoccupations of a baby-boom generation that never thought it would age. Make no mistake, “The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel” is the tip of a trend. (“Hope Springs,” about an aging married couple that seeks out therapy to rekindle their love life, is already on its heels, in the theaters). Now the boomers are on the cusp of collecting Medicare and anxious about how they will navigate the “shipwreck”—as Charles DeGaulle characterized it—of growing old.

***************

Is it just me, or is the County Fair not what it used to be? The Cuyahoga County Fair, in Berea, to which I have gone almost every August I have lived here, seemed thin to me this year. Even the agricultural exhibits that are the backbone of a county or state fair struck me as a little tired. Certainly fairs are not what they were when we were kids. I didn’t go inside to see the “freak” shows in Berea—the “Human Pretzel”, etc—but I suspect these are a pale imitation of the freak shows of yesteryear. And no doubt that is probably for the best. (I still wonder if I am making up in my mind some of the stuff I thought I saw, or that my college chums said they saw, at the county fair in the mid-size Pennsylvania town where I went to college thirty years ago.) Still, the sense of the riotous abundance of American life—including a riotous abundance of weirdness—is what I look for in a fair.

Maybe I just went too early in the week. And now it’s over. The moveable feast that is a state or county fair is a staple of summer, and the end of it spells the end of the season, a winding down to a darkening period when whatever abundance we have been blessed with must carry us through to the next county fair.

************

“That cat’s going to be at my funeral,” I used to say a lot, but I don’t anymore because the cat died this summer, breaking everyone’s heart. Patches was a beloved orange and white one who showed up at the house 11 or 12 years ago and lived the rest of his life outside, sheltering in the garage in the winter (and elsewhere in the neighborhood wherever he was welcome), sleeping on porches, catching birds and rodents (and chowing down on store-bought stuff we left out for him), and generally enjoying being a cat.

Twelve Cleveland winters—he seemed to be indestructible—and in the end it was the summer heat that did him in. I think he caught an infection or something; he stopped eating and the last I saw him he was skin and bones. One of the contractors working on the roof of my daughter’s house expressed amazement that the cat showed up and stood under a shower of water when the guys were hosing down the roof—odd behavior and a sign that he was probably burning up.

A few days later there was an ominous odor from under the house and Mom and a friend raked his body out from under the porch. Placed it in a blanket and buried Patches out back by the garage where he had spent so much of his life. My daughter and I were out of town and on the drive back her mother gave her the news. She cried copiously.

*************

In the sweltering church on a Saturday afternoon in July when my friend was eulogized, the pastor read a passage from Paul’s letter to the church at Philippi.

“In your relationships with one another, have the same mindset as Christ Jesus who, being in very nature God, did not consider equality with God something to be used to his own advantage; rather, he made himself nothing by taking the very nature of a servant, being made in human likeness. And being found in appearance as a man, he humbled himself by becoming obedient to death —even death on a cross….Therefore, my dear friends, as you have always obeyed—not only in my presence, but now much more in my absence—continue to work out your own salvation with fear and trembling…”

And later….

“Finally, brothers, whatever is true, whatever is noble, whatever is right, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is admirable--if anything is excellent or praiseworthy--think about such things…”

I think my faith now amounts to a thing of shreds and patches, but sometimes something wakes me up. Maybe it had something to do with perspiring in that sweltering church, guzzling bottles of water from the ushers, and listening to eulogies for a woman who had spent the last year and a half of her life confined to an apartment and an oxygen machine. Work out your own salvation in fear and trembling. If the Christian faith is the miracle its adherents say it is then it is miraculous because it exalts the human likeness, and has its feet planted on terra firma, in the here and now of human living, growing old and dying. There is a contemplative Christianity, to be sure, but even the contemplative lives in the teeth of the awesome and tremble-inducing facts of our brief livelihood, eventual decline and decay, and inevitable death. And it is in the teeth of those facts that we must work out our own salvation, find our own way to the mountaintop, drawing from the raw materials of our own human story, from the riotous abundance of our own unique freak show of a life. Here is contentious, argumentative, perfectionist Paul—whose life as a Pharisaic Jew was spent earnestly and self-punishingly trying to work out a formula for righteousness—telling his correspondents that alas, there is no formula.

|

| Rainbow over Lakewood, Ohio. Photo by Jim O'Brien, courtesy The Lakewood Observer |

Labels:

aging,

autumn,

county fairs,

death,

summer,

the Apostle Paul

Wednesday, August 8, 2012

"Watergate" by Thomas Mallon: Hopelessly Human

The scandal known as “Watergate” that ended thirty eight years ago today with the resignation of Richard Nixon has had enormous impact, mainly a bad one, on how all Americans regard politicians, government, and the very calling of public service. Although it brought down a prominent figure of the right, and was regarded at the time as a victory of the liberal left, the scandal’s most lasting impact has probably been to implant in millions of American minds a deep distrust in organs of American government. The seeds of the Tea Party’s bitter hatred of “Washington” can be found in Watergate.

The scandal known as “Watergate” that ended thirty eight years ago today with the resignation of Richard Nixon has had enormous impact, mainly a bad one, on how all Americans regard politicians, government, and the very calling of public service. Although it brought down a prominent figure of the right, and was regarded at the time as a victory of the liberal left, the scandal’s most lasting impact has probably been to implant in millions of American minds a deep distrust in organs of American government. The seeds of the Tea Party’s bitter hatred of “Washington” can be found in Watergate.

But the episode has “already” accumulated the dust of a distant episode most, or certainly many, Americans can only dimly recall, a quaint relic in the nation’s attic. To recall the names of the period is like coming upon an old middle school year book inscribed with wishes from long lost classmates to “have a great summer!” John Dean. John Ehrlichman. Bob Haldeman. Howard Hunt. Who remembers Tony Ulasewicz, the bagman who delivered wads of cash as “hush money” to Howard Hunt’s wife and talked like a Damon Runyon character when testifying before the Senate investigative committee?

It is a bittersweet relic for some of us who were just becoming politically aware when the scandal was making headlines. I was fourteen when Nixon resigned, and I grew up outside of Washington in a family that talked politics at the dinner table. (And to add to the kitchiness of this recollection, the summer before I had a paper route delivering the Washington Post, where Woodward and Bernstein were regularly taking the President to the cleaners.) Washington at the time had a lively party circuit, hosted by fashionable Georgetown matrons, that was chronicled in the Post’s “Style” section. But in many other ways it was still striving to outgrow John Kennedy’s description of the nation’s capital as a city of “southern efficiency and northern charm.” It was a profoundly segregated city and the ruins of riots six years prior to the President’s resignation still rendered vast stretches of real estate east of the Capitol a no-man’s land (at least for white people).

Thomas Mallon’s novel, “Watergate,” brings it all back to life, intelligently and clairvoyantly. They are all there—the burglars Gordon Liddy and Howard Hunt and the Cubans, Dean and Haldeman and Jeb Magruder and John and Martha Mitchell. Nixon and butt-kissing Henry Kissinger. The whole cast.

His story is a comedy, or a tragi-comedy in which a vast national calamity grows out of a complex history of miscues, crossed signals and half-hearted intentions, a comedy haphazardly propelled by personal (rather than public) motives, misunderstandings and misconnections. It is a tale of humans in positions of power being hopelessly human, and so his hypothesis--although wildly imaginative--is entirely plausible. John Mitchell, the attorney general, is hopelessly in love with and hopelessly distracted by his mentally ill and alcoholic wife Martha, and is depicted as fatally deferring on a decision about whether to fund the nit-witted Gordon Liddy and his confederates in their plans for subverting the election. Nixon himself is depicted as more of a fumbling neurotic than a paranoid calculator. “I listen to myself on the tapes and hear myself trying to sound like I know more than I really do,” he tells his wife tearfully, when the gig is up.

His story is a comedy, or a tragi-comedy in which a vast national calamity grows out of a complex history of miscues, crossed signals and half-hearted intentions, a comedy haphazardly propelled by personal (rather than public) motives, misunderstandings and misconnections. It is a tale of humans in positions of power being hopelessly human, and so his hypothesis--although wildly imaginative--is entirely plausible. John Mitchell, the attorney general, is hopelessly in love with and hopelessly distracted by his mentally ill and alcoholic wife Martha, and is depicted as fatally deferring on a decision about whether to fund the nit-witted Gordon Liddy and his confederates in their plans for subverting the election. Nixon himself is depicted as more of a fumbling neurotic than a paranoid calculator. “I listen to myself on the tapes and hear myself trying to sound like I know more than I really do,” he tells his wife tearfully, when the gig is up.

The central figure in the story is Fred LaRue, a barely recallable figure who nevertheless was at the heart of the scandal. A top fundraiser among southern conservatives that Nixon cultivated for their resentment over civil rights, Larue was the one who scoured up the dough to give to Ulasewicz to give to the burglars to keep them quiet. But LaRue—in Mallon’s telling—also carries a terrible secret from his childhood, one that will propel his duplicitous actions in the cover-up and that emerges as central to answering an enduring mystery about the scandal: Why did the burglars wiretap the Democratic National Committee to begin with, and what were they looking for?

An easy enough way to imagine yourself into Mallon’s understanding of history is to think back to the last time a relationship, a friendship, or a marriage dissolved. There is the story you tell your friends and relatives, the story you have sold to yourself. She likes Chinese, you like Italian. You just weren’t compatible. It’s true, or true enough. But there is another, more complicated story you know in your heart. There is (though you cringe to recall it) that lame, dumb thing you whispered to her on the pillow one night. You thought you were being funny and original and edgy, and in fact you thought she was asleep. But she wasn’t and ten days later, as the two of you were preparing to go to a party and she was in the middle of a bitch-fit about a run in her stocking, she threw the remark back in your face. A chilly silence descends over the two of you. At the party you avoid her and find yourself trapped in a conversation with an expert in Sanskrit who is desperate to go home with someone tonight. The Sanskrit expert is not at all your type and a bore besides, and you’ve been avoiding your (wife, girlfriend, partner, friend) mainly because you are hot with embarrassment. But you’ve had a few drinks and you really need to get to the bathroom to take a piss and when you make a move to go, the Sanskrit expert simultaneously moves in the same direction causing the two of you to bump into each other in what looks like a kiss, or a hug, or something kind of, sort of affectionate. Your partner of course assumes you were making a pass at the Sanskrit expert and after the party a vicious alcohol-fueled fight ensues over this “incident”. Five days later you are determined to set things right by surprising her at home with flowers and a home-made dinner. But on the night of the big surprise she is called to an emergency baby-sitting assignment for her hard-pressed, single-mom sister whose kid has dyslexia and ADHD. On the phone you are crestfallen, and you actually really like and admire the single-mom sister, but the end is spelled when you absent-mindedly let slip the remark, “well, doesn’t that just fucking figure.”

Let’s face it, you can’t tell that story to the relatives, and they don't want to hear it anyway. What they want to hear is the story about how she likes Chinese, you like Italian and, well, you just weren’t compatible.

In just such a fashion does Mallon render the history of Watergate. This is history from the inside--history written by the random chaos of the human heart--and the proof of the intelligence of his story is the degree to which this tall tale is entirely believable. But this should not at any cost be confused with “conspiracy theory,” which is an effort not to understand random complexity but to reduce historical events to a child’s building blocks. The people who think that 9/11 was an inside job, for instance, aren’t interested in comprehending what happened on and before that terrible day; they are in full flight in the opposite direction, grasping at a fairy tale that will release them—and all of us—from the terrible randomness and uncertainty of history.

If I have a complaint—and this is a tepid one for a really good read—it is that this is history without culprits and correspondingly without consequences, beyond the fate of the vain and shallow characters who inhabit it. But in fact, there were culprits-- surely Richard Nixon and his carpet bombing madman Secretary of State Henry Kissinger were a most noxious couple of power-sick fellows to be running the world’s most successful democracy. And there have most certainly been consequences, which are everywhere around us today to see. Monday, July 16, 2012

The World Outside Your Door: Kelly's Island

“The charge of an island fortress cannot be something a man gives up without ambivalent feelings…”

Joan Didion, “Rock of Ages”

Joan Didion was writing, back then in 1967, about the island of Alcatraz, only recently at that time emptied of its inhabitants when the famous prison was closed. Al Capone and the notorious “Birdman” had once made their residence there, but when Ms. Didion paid a visit the sole inhabitant was a lone federal employee, paid to do what minimal upkeep was necessary, who lived there with his wife and dog. As recorded in an austere and incandescently beautiful essay published in her classic 1960s collection "Slouching Toward Bethlehem," the writer found that she did not want to leave, that she would have stayed if only someone had asked her to. “It is not an unpleasant place to be, out there on Alcatraz with only the flowers and the wind and a bell buoy moaning and the tide surging through the Golden Gate, but to like a place like that you have to want a moat. I sometimes do, which is what I am talking about here.”

An island has its own spirit, a “mentality” conditioned by the surrounding waters that appeals to solitaries, and that would invariably solicit Ms. Didion’s literary instincts, honed to a fine point by her self’s fragile sense of apartness. It is not at all coincidental that she wrote with such keen insight about life on Hawaii in the decades after Pearl Harbor, still haunted even in the 60's--as the body bags from Vietnam arrived at Oahu--by war. You have to want a moat.

Indeed, you do. I’m out here today in the middle of Lake Erie, on Kelly’s Island. Happy as a clam. Happy like a fool. After the hour-and-an-a-half drive to Marblehead, and the twenty-five minute ferry across the Lake, I arrived at the dock and walked to the bed-and-breakfast with my bags. Checked into my room and rented a bicycle. A pink one! The pink bikes had baskets, the black bikes did not, and I wanted a basket damnit! In case I found—I don’t know—buried treasure or something. (As the lady at the desk said “It’s just a color.”) I rode around the island on a pink bicycle hoping to find buried treasure.

Indeed, you do. I’m out here today in the middle of Lake Erie, on Kelly’s Island. Happy as a clam. Happy like a fool. After the hour-and-an-a-half drive to Marblehead, and the twenty-five minute ferry across the Lake, I arrived at the dock and walked to the bed-and-breakfast with my bags. Checked into my room and rented a bicycle. A pink one! The pink bikes had baskets, the black bikes did not, and I wanted a basket damnit! In case I found—I don’t know—buried treasure or something. (As the lady at the desk said “It’s just a color.”) I rode around the island on a pink bicycle hoping to find buried treasure.

Kelly’s Island. It’s hardly Alcatraz, or the Hawaiian Islands. It’s a resort spot, with a state park, and is teeming with sunburnt well-to-do types, teenagers, kids with ice cream cones, putt-putt golfers, fun-in-the-sun partiers and all the rest. (But it’s not Put-In-Bay, which I gather is some kind of Gomorrah, but one where everyone is too drunk to actually do anything wicked.)

Kelly’s Island. It’s hardly Alcatraz, or the Hawaiian Islands. It’s a resort spot, with a state park, and is teeming with sunburnt well-to-do types, teenagers, kids with ice cream cones, putt-putt golfers, fun-in-the-sun partiers and all the rest. (But it’s not Put-In-Bay, which I gather is some kind of Gomorrah, but one where everyone is too drunk to actually do anything wicked.)

And there is an indigenous, year-round resident life here—a few churches, a school, an AA meeting or two, a municipal hall. The first school on the Island was built in 1837, and the school that today stands on Division Street in the middle of the Island was built in 1901. But I was sad to read on the website of the Kelly’s Island School, that it would be suspending operations; plans were in the works to transport the handful of Island children to schools on the mainland. (Speaking of boyhood fantasies, what child would not like to ride a ferry across a Great Lake to get to school?) The marquee outside the school lists the names of what I surmise are the graduates—all five of them.

And there is an indigenous, year-round resident life here—a few churches, a school, an AA meeting or two, a municipal hall. The first school on the Island was built in 1837, and the school that today stands on Division Street in the middle of the Island was built in 1901. But I was sad to read on the website of the Kelly’s Island School, that it would be suspending operations; plans were in the works to transport the handful of Island children to schools on the mainland. (Speaking of boyhood fantasies, what child would not like to ride a ferry across a Great Lake to get to school?) The marquee outside the school lists the names of what I surmise are the graduates—all five of them.

That’s where I’m at and happy like a fool.

Joan Didion, “Rock of Ages”

Joan Didion was writing, back then in 1967, about the island of Alcatraz, only recently at that time emptied of its inhabitants when the famous prison was closed. Al Capone and the notorious “Birdman” had once made their residence there, but when Ms. Didion paid a visit the sole inhabitant was a lone federal employee, paid to do what minimal upkeep was necessary, who lived there with his wife and dog. As recorded in an austere and incandescently beautiful essay published in her classic 1960s collection "Slouching Toward Bethlehem," the writer found that she did not want to leave, that she would have stayed if only someone had asked her to. “It is not an unpleasant place to be, out there on Alcatraz with only the flowers and the wind and a bell buoy moaning and the tide surging through the Golden Gate, but to like a place like that you have to want a moat. I sometimes do, which is what I am talking about here.”

An island has its own spirit, a “mentality” conditioned by the surrounding waters that appeals to solitaries, and that would invariably solicit Ms. Didion’s literary instincts, honed to a fine point by her self’s fragile sense of apartness. It is not at all coincidental that she wrote with such keen insight about life on Hawaii in the decades after Pearl Harbor, still haunted even in the 60's--as the body bags from Vietnam arrived at Oahu--by war. You have to want a moat.

Indeed, you do. I’m out here today in the middle of Lake Erie, on Kelly’s Island. Happy as a clam. Happy like a fool. After the hour-and-an-a-half drive to Marblehead, and the twenty-five minute ferry across the Lake, I arrived at the dock and walked to the bed-and-breakfast with my bags. Checked into my room and rented a bicycle. A pink one! The pink bikes had baskets, the black bikes did not, and I wanted a basket damnit! In case I found—I don’t know—buried treasure or something. (As the lady at the desk said “It’s just a color.”) I rode around the island on a pink bicycle hoping to find buried treasure.

Indeed, you do. I’m out here today in the middle of Lake Erie, on Kelly’s Island. Happy as a clam. Happy like a fool. After the hour-and-an-a-half drive to Marblehead, and the twenty-five minute ferry across the Lake, I arrived at the dock and walked to the bed-and-breakfast with my bags. Checked into my room and rented a bicycle. A pink one! The pink bikes had baskets, the black bikes did not, and I wanted a basket damnit! In case I found—I don’t know—buried treasure or something. (As the lady at the desk said “It’s just a color.”) I rode around the island on a pink bicycle hoping to find buried treasure.  Kelly’s Island. It’s hardly Alcatraz, or the Hawaiian Islands. It’s a resort spot, with a state park, and is teeming with sunburnt well-to-do types, teenagers, kids with ice cream cones, putt-putt golfers, fun-in-the-sun partiers and all the rest. (But it’s not Put-In-Bay, which I gather is some kind of Gomorrah, but one where everyone is too drunk to actually do anything wicked.)

Kelly’s Island. It’s hardly Alcatraz, or the Hawaiian Islands. It’s a resort spot, with a state park, and is teeming with sunburnt well-to-do types, teenagers, kids with ice cream cones, putt-putt golfers, fun-in-the-sun partiers and all the rest. (But it’s not Put-In-Bay, which I gather is some kind of Gomorrah, but one where everyone is too drunk to actually do anything wicked.)

But an island is an island and it appeals to a certain type, appeals I suppose to some kind of universal boy fantasy of a place you could claim for your own, find buried treasure beneath, build a moat around, stand on the beach with a flaming sword and defend against any who dared to cross the waters. How to explain this? Well, first of all, it’s small enough to traverse in its entirety on a bicycle in under an hour. But large and diverse enough in landscape and topography that you can forget you are on an island, surrounded by water. Out in the middle of the island are woods and fields and quaint, lonely country homes and for all you know you could be in rural southern Ohio, or Missouri. There’s history on the Island, human and geological. The glacial grooves are a large fossil remnant of the Wisconsin Glacier, which moved across this territory 25,000 years ago in southwesterly direction, then receded 10,000 years later, leaving behind some 50 yards of grooved stone, only uncovered in the 1800s. Much of the human history on Kelly’s dates from the 19th century and—if I was not misreading the dates on some of the stones in the Island’s graveyard—even the 18th.

And there is an indigenous, year-round resident life here—a few churches, a school, an AA meeting or two, a municipal hall. The first school on the Island was built in 1837, and the school that today stands on Division Street in the middle of the Island was built in 1901. But I was sad to read on the website of the Kelly’s Island School, that it would be suspending operations; plans were in the works to transport the handful of Island children to schools on the mainland. (Speaking of boyhood fantasies, what child would not like to ride a ferry across a Great Lake to get to school?) The marquee outside the school lists the names of what I surmise are the graduates—all five of them.

And there is an indigenous, year-round resident life here—a few churches, a school, an AA meeting or two, a municipal hall. The first school on the Island was built in 1837, and the school that today stands on Division Street in the middle of the Island was built in 1901. But I was sad to read on the website of the Kelly’s Island School, that it would be suspending operations; plans were in the works to transport the handful of Island children to schools on the mainland. (Speaking of boyhood fantasies, what child would not like to ride a ferry across a Great Lake to get to school?) The marquee outside the school lists the names of what I surmise are the graduates—all five of them.That’s where I’m at and happy like a fool.

Monday, February 20, 2012

Injured: The Pointlessness of Physical Pain, The Madman Below My Ear, A Laying on of Hands, and Two Final Thoughts

No pain, no gain, goes the modern trope.

I think, I hope, I believe, that this is emphatically and undeniably true when it comes to the pains of the spirit, to emotional suffering, to living through and beyond such tragedies of human life as divorce, the death of loved ones, the disappointment engendered by people one thought of as friends, the realization that one’s own life is short and bound on all sides by compromise. And so on. Like most people my age, I have come upon some of this and it is a source of much wonderment to me that however much some of this experience was a source of real, emotionally painful bewilderment—some of it quite nightmarish—it is also true that all of it has made me somehow better, more human, emotionally richer, wiser, more mature, less one dimensional. It has caused me to look at my own contribution to things that have gone wrong, has (occasionally) made me more forgiving, and—the very best thing I think—has caused me to move out of my comfort zone, try new things, to go in new directions. It strikes me that this phenomenon is the source of all philosophy, and it has a pedigree in most religious traditions. “[W]e rejoice in our sufferings,” the apostle Paul says famously in Romans, “knowing that suffering produces endurance, and endurance produces character, and character produces hope, and hope does not disappoint us…”

But I wonder…Can the same be said of physical pain? I have been mercifully healthy (for the most part) all of my life, and all but entirely free of any really physically painful conditions. But very recently, as a result of the combination of several exercise activities, I have, in the parlance of sports announcers, “sustained an injury.” Actually, it was an aggravation of an injury I “sustained” four months ago, to my shoulder. Turns out (as revealed by an X-ray) I have some arthritis somewhere where the arm bone meets the shoulder socket. Stress on this mechanism inflamed the arthritis. The latter causes its own severe discomfort, but the inflammation also impinges on a nerve that radiates from the neck down to the middle of the forearm. The result is that in addition to the dull ache of the inflamed joint, there is a more acute, piercing pain very similar to sciatica—the condition wherein nerves that radiate down one of the legs are impinged upon by prolapsed bones in the lower spinal cord.

How to describe the full effect of this orthopedic mischief in my shoulder? It is like having an extremely furious and wholly insane individual seated slightly below your ear and screaming at an almost impossibly high pitch, in periodic and unpredictable intervals. Another image I take away from the experience is that of a cartoon bully, perfectly mute and inarticulate, relentlessly punching you in the face (in my case, in the shoulder) for the joyless pleasure of letting you know he can do it. Someone I know made the smart remark that the nearer pain is located towards your head, the more distracting it becomes, an observation with which anyone who has had a severe toothache can resonate. For a day or two there before I got to the doctor’s, I think—no, I know—I was slightly nuts. My perception of reality was continuously fractured, having to tend every few minutes to the screaming madman below my ear, so that I could focus on nothing—including the work for which I get paid—for more than a few minutes. My house became even more disheveled than usual because such simple, arm-and-shoulder dependent tasks as washing the dishes and sweeping the kitchen floor caused me, after twenty minutes, to wish I had a chain saw with which to disengage my arm from my body. I have had to temporarily suspend those things—a mediocre tennis game, a little yoga, and a much-less-than-mediocre piano practice—that give me a lot of pleasure.

On the short end of recovery now, I can find almost nothing positive about the experience. It was diminishing in every way. It taught me—thanks very much!—that I am not the man I used to be and can’t do the things I did ten or twenty years ago. Swell. Any more positive feelings—gratitude for doctors and nurses and therapists and for modern medicine, thankfulness for pain free use of my limbs—were the result (make note!) of recovery, of release and relief from pain. As for those times when my shoulder and arm were at their most opinionated, believe me when I say that gratitude was the farthest thing from my spirit. I would regard you and everyone else who came within my path as an imbecile determined to make my life more miserable than it already was.

Yeah, yeah….I did my manly best to suck all this up and keep it indoors and I would like to think I was more or less successful. Whether I was or not, you will have to ask those few people who had to deal with me up close. But the truth, I know, is that the entire experience reduced me to something like a moderately intellectually disabled, immoderately immature teenager with an attention deficit disorder.

All of which has caused me to think about, as a contrast to the paradoxical usefulness of emotional suffering, the remarkable pointlessness, the uselessness, of physical pain. And the imperative to vanquish it, whenever and wherever it exists. It is one human condition that seems to lead nowhere, that points to nothing other than the most brute facts of existence—you are small and finite and at the mercy of nature—without offering something redeeming in return; or else the return is diminishing and not commensurate with the cost. Physical pain is universal—no one will escape it entirely—and it may be that what can be said for pain is that it reminds you what it is like not to be in pain. But, again, that presupposes a recovery, which may not necessarily be in the natural course of things and may be dependent on someone who cares enough (or is paid well enough) to help relieve you. And anyway, I don’t want to give too much ground on this, because the bargain (if that’s what it is) seems to me to be a swindle—you lose too much and become too diminished in the transaction. Hitchens dealt with this in one of his last pieces before his painful death from esophageal cancer, taking on that cliché about things that don’t kill you making you stronger. (Evidently, some things can make you weaker and then will kill you anyway.)

And on the side of recovery one has to credit the work-a-day diligence of those doctors and nurses and therapists whose job it is to vanquish pain. When I first visited my doctor four months ago with my initial, less severe, experience of this injury, this doctor—whom I have come to trust and revere—discussed various treatment options. Physical therapy was a given, but there were medicines, anti-inflammatories of varying potencies to consider, along with their possible side effects. At the time I recall that when I showed up at the office my symptoms had somewhat mysteriously subsided, so there was some legitimate question whether a prescription was necessary. And I recall that as he was reviewing my chart, and without quite looking at me, he wondered in a seemingly off-hand, and possibly whimsical way, if perhaps “a laying on of hands” would be enough. Whimsical though it may have been, I am quite sure he was in no way diminishing the severity of what I had experienced. Smart doctors, I think, know all about the “laying on of hands,” know all about patients who “mysteriously” get better when they get a little attention, a little assurance that they aren’t going to be killed by what they experience. Who has not felt better, a little bit anyway, entering the work-a-day hum of a doctor’s office and knowing suddenly that so much trained, perfected expertise cannot but prevail against some trifling symptom?

I did get a prescription, then, and took some physical therapy, but realize now I didn’t take it seriously enough. Which explains why I was back four months later. This time, I saw one of my doctor’s colleagues, a sharp, friendly young woman who intuited quickly how agonized I was, tried to amuse me with some humor, laughed readily at my own attempts to make light, wrote me a prescription for a short course of low-dose prednisone and some extended physical therapy, invited me to call at the drop of a hat, assured me that if some more specialized attention was necessary it would be ordered immediately, and sent me on my way. Once again, my kindest feelings about physical pain are all on the side of those who do what they can to get rid of it.

Two last thoughts: The pointlessness of physical pain, once you have experienced it yourself, seems to me to be the last word anyone should need on why not to inflict it on anyone else, including one’s worst enemies. What cause, short of the most immediate need for self-defence, is worth becoming that cartoon bully, the messenger that life is an empty shell?

And then this: some 15 years ago, I wrote a little bit in a professional way about advocacy, on the part of some physicians who specialize in pain management, for the legalized use of heroin in terminally ill patients for whom morphine isn’t enough. I believe its use has long been legal in the United Kingdom, but I am entirely unsure of its legal status in the United States and have long since lost track of this subject. Back then, the cause had a seemingly unlikely champion in William F. Buckley (seemingly, I say, because Buckley could be counted on to take on some esoteric subjects and adopt some surprising stances). In any case, he was for it and so am I. There is an argument against this, about the dignity of human beings in their last days, about the integrity of human suffering, and about how people ought perhaps not to be subject to treatments in death they would never consent to in less dire circumstances. It is a potent and valuable and substantive and elegant argument, and I say the hell with it. And I say: Vanquish the pain! Because the last thing anyone needs to be reminded of, particularly when they are dying, is about pointlessness.

Thursday, February 9, 2012

The Sadness of Men Trying to Keep Up: The Descendants

Anyone left who hasn’t seen The Descendants has almost surely seen the trailers, in which George Clooney—playing a wealthy Hawaiian lawyer and landowner named Matt King—is running. And running, in various ways, he is throughout this beautiful and sad and funny film. He runs, in sandals, from his house to a neighbor’s to demand what they know about the affair his gravely injured wife was conducting before her boating accident; he runs up and down a beach in search of the intruder in his marriage. And, figuratively, he is running to keep up with--or keep ahead of--a torrent of misfortune; and running to catch up with the children he has allowed, in the conventional male way, to run ahead of him while he was busy earning the privileges (private schools, a lush Oahu island home) that allowed him to think it was okay for him to be, as he says, “the back-up parent.”

It is not at all incidental that in those scenes in which he is literally running, he looks distinctly like someone who is, well, Not A Runner. Pumps his arms a little too fast, strides a little too short. (And any daily runner would have a pair of sneakers, at least a pair of old beaters, to slap on in the case of an emergency like needing to run down the canyon road to find out from the neighbors who his wife was screwing behind his back.)

The more I think about this movie the more I think it is, at least in part, a story about male competence, and incompetence. And that it is a far prettier, smarter, and less pretentious story (one that strives, certainly, to be more Hollywood-mainstream) than Sideways, also directed by Alexander Payne and also about the woes and competencies and incompetencies of middle-aged men.

The sadness of guys, trying to keep up. They, we, seem to be on the ropes, everywhere. Matt King is on the ropes and as imperfect as his jogging appears, he seems to be even more less-than-perfectly-competent at almost everything else he is trying to keep up with. Most especially his daughters, the younger of whom is texting cruel and “inappropriate” comments to classmates, and the older of whom, Alex, is honing the conventional stance of snide cynicism teenage girls seem to have toward all adults (perhaps, especially males) and selectively their parents (perhaps particularly their fathers, for whom they also yet reserve a touchingly ill-concealed desire to love, if only dad wouldn’t act so ridiculously embarrassing). Alex is also working on a possibly incipient case of alcoholism. More about this particular teenager and the actress who portrays her later.

But for all his imperfection, Matt is also, through and through, a Pretty Good Guy, doing his best. I had the interesting, passing thought early in this movie that George Clooney didn’t seem to be working too hard, that maybe this role wasn’t too demanding. Which either suggests that he knows all about being Matt King, or that he was doing a piece of very fine acting. A female friend I saw this with commented later that (hold your breath for a surprise) she normally finds George Clooney attractive—but didn’t find him attractive in this film; by which I think she means to suggest that the actor had made himself in his role somehow physically unattractive, which would suggest a very, very, very good acting job indeed.

But I think I understand that. Because the attractiveness, especially the sexual allure, of men is so allied with the projection of confidence, of competence. And when their need for the affirmation of others becomes too acute they can seem to be un-manned. Yet (and I know these generalizations about gender can seem tiresome) men never seem to need too much. My father, whenever his birthday rolled around, would tell us as a kind of regular joke whenever we asked him what he wanted that he would be satisfied with a “kind word.”

Matt King is a man sorely in need of a kind word. The most memorable scene and the one most emblematic of this very competent but out-of-his-depth man’s need for a consoling word is after the decision has been made—mandated by an advance directive—that life support will be withdrawn and that his wife will die. Friends and immediate family are invited to bid goodbye to the woman. Her father, Matt’s father-in-law, is a hard type and something of a knucklehead who uses the occasion to berate Matt for his failings. Whereupon daughter Alex speaks up and says, “Hey my father’s doing a really great job in a difficult situation.”

This is the occasion of a really priceless piece of acting when George Clooney is seen doing a double, or triple, or quadruple or maybe quintuple take at his daughter, madly desiring in a situation of impossible protocol, to wrap his arms around the girl and hug her to death. I certainly wanted to.

About this actress, Shailene Woodley. She has received richly deserved attention for her role, but I think she was robbed of an Academy Award nomination for best supporting actress. Because this young lady nailed this role to the wall. The mouthiness—what is it about teenage girls that causes their angst to come screaming through their teeth?—the insouciance, and then the casual, unexpected brilliance and grace that makes you wonder if maybe they really are (as they assume) smarter than you. And the way they mature so much faster than you could have anticipated, as Alex does progressively in this film.

I love the traditional Hawaiian music that permeates the movie. The resolution of the land deal at the end makes sense in a way I didn’t think it would. And in the end Matt and his daughters are lounging in a sofa watching a movie being narrated by Morgan Freeman. I didn't catch it at the time, but read later that the movie is March of the Penguins. About mammals who learn through adaptive evolution how to nurture their offspring in what seems like impossible circumstances.

Thursday, January 26, 2012

"Anxiously Awaiting an Answering Voice Amid Utter Silence"

I have for the most part, written off reading Charles Krauthammer because he has become as predictable as death and taxes in his disparagement of everything that Barack Obama says or does or tries. And he is one of the most consistent purveyors of the right wing line about Obama-as-Off-the-Grid: redistributing income, coddling and apologizing to our enemies, disavowing American exceptionalism, and shamelessly pandering to the progressive left. (Never mind how disappointed the progressive left has been in Obama). And Krauthammer is unrepentant about the Iraq war and in general the entire neo-con approach that reigned for eight (ruinous) years.

But I have come across, a few weeks late, this brilliant and beautiful column by Krauthammer about the search for intelligent life in the cosmos. Money quote:

“As the romance of manned space exploration has waned, the drive today is to find our living, thinking counterparts in the universe. For all the excitement, however, the search betrays a profound melancholy — a lonely species in a merciless universe anxiously awaits an answering voice amid utter silence.”

And this:

“…this silent universe is conveying not a flattering lesson about our uniqueness but a tragic story about our destiny. It is telling us that intelligence may be the most cursed faculty in the entire universe — an endowment not just ultimately fatal but, on the scale of cosmic time, nearly instantly so.”

And, finally, this:

“Rather than despair, however, let’s put the most hopeful face on the cosmic silence and on humanity’s own short, already baleful history with its new Promethean powers: Intelligence is a capacity so godlike, so protean that it must be contained and disciplined. This is the work of politics — understood as the ordering of society and the regulation of power to permit human flourishing while simultaneously restraining the most Hobbesian human instincts.

“There could be no greater irony: For all the sublimity of art, physics, music, mathematics and other manifestations of human genius, everything depends on the mundane, frustrating, often debased vocation known as politics (and its most exacting subspecialty — statecraft). Because if we don’t get politics right, everything else risks extinction.

“We grow justly weary of our politics. But we must remember this: Politics — in all its grubby, grasping, corrupt, contemptible manifestations — is sovereign in human affairs. Everything ultimately rests upon it.

“Fairly or not, politics is the driver of history. It will determine whether we will live long enough to be heard one day. Out there. By them, the few — the only — who got it right.”

Here’s the article in full. http://jewishworldreview.com/cols/krauthammer123011.php3

And it follows another really brilliant piece he wrote about the discovery of neutrinos that travel faster than the speed of light. http://jewishworldreview.com/cols/krauthammer100611.php3

I wonder if Krauthammer could be persuaded to give up writing about politics and take up being a full-time science writer.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)