No pain, no gain, goes the modern trope.

I think, I hope, I believe, that this is emphatically and undeniably true when it comes to the pains of the spirit, to emotional suffering, to living through and beyond such tragedies of human life as divorce, the death of loved ones, the disappointment engendered by people one thought of as friends, the realization that one’s own life is short and bound on all sides by compromise. And so on. Like most people my age, I have come upon some of this and it is a source of much wonderment to me that however much some of this experience was a source of real, emotionally painful bewilderment—some of it quite nightmarish—it is also true that all of it has made me somehow better, more human, emotionally richer, wiser, more mature, less one dimensional. It has caused me to look at my own contribution to things that have gone wrong, has (occasionally) made me more forgiving, and—the very best thing I think—has caused me to move out of my comfort zone, try new things, to go in new directions. It strikes me that this phenomenon is the source of all philosophy, and it has a pedigree in most religious traditions. “[W]e rejoice in our sufferings,” the apostle Paul says famously in Romans, “knowing that suffering produces endurance, and endurance produces character, and character produces hope, and hope does not disappoint us…”

But I wonder…Can the same be said of physical pain? I have been mercifully healthy (for the most part) all of my life, and all but entirely free of any really physically painful conditions. But very recently, as a result of the combination of several exercise activities, I have, in the parlance of sports announcers, “sustained an injury.” Actually, it was an aggravation of an injury I “sustained” four months ago, to my shoulder. Turns out (as revealed by an X-ray) I have some arthritis somewhere where the arm bone meets the shoulder socket. Stress on this mechanism inflamed the arthritis. The latter causes its own severe discomfort, but the inflammation also impinges on a nerve that radiates from the neck down to the middle of the forearm. The result is that in addition to the dull ache of the inflamed joint, there is a more acute, piercing pain very similar to sciatica—the condition wherein nerves that radiate down one of the legs are impinged upon by prolapsed bones in the lower spinal cord.

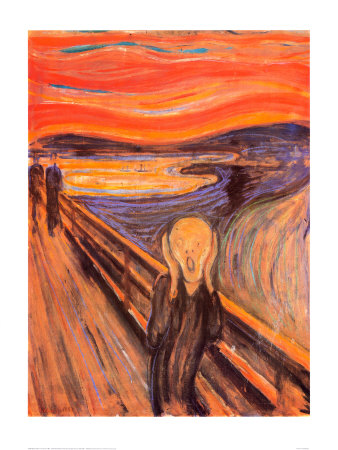

How to describe the full effect of this orthopedic mischief in my shoulder? It is like having an extremely furious and wholly insane individual seated slightly below your ear and screaming at an almost impossibly high pitch, in periodic and unpredictable intervals. Another image I take away from the experience is that of a cartoon bully, perfectly mute and inarticulate, relentlessly punching you in the face (in my case, in the shoulder) for the joyless pleasure of letting you know he can do it. Someone I know made the smart remark that the nearer pain is located towards your head, the more distracting it becomes, an observation with which anyone who has had a severe toothache can resonate. For a day or two there before I got to the doctor’s, I think—no, I know—I was slightly nuts. My perception of reality was continuously fractured, having to tend every few minutes to the screaming madman below my ear, so that I could focus on nothing—including the work for which I get paid—for more than a few minutes. My house became even more disheveled than usual because such simple, arm-and-shoulder dependent tasks as washing the dishes and sweeping the kitchen floor caused me, after twenty minutes, to wish I had a chain saw with which to disengage my arm from my body. I have had to temporarily suspend those things—a mediocre tennis game, a little yoga, and a much-less-than-mediocre piano practice—that give me a lot of pleasure.

On the short end of recovery now, I can find almost nothing positive about the experience. It was diminishing in every way. It taught me—thanks very much!—that I am not the man I used to be and can’t do the things I did ten or twenty years ago. Swell. Any more positive feelings—gratitude for doctors and nurses and therapists and for modern medicine, thankfulness for pain free use of my limbs—were the result (make note!) of recovery, of release and relief from pain. As for those times when my shoulder and arm were at their most opinionated, believe me when I say that gratitude was the farthest thing from my spirit. I would regard you and everyone else who came within my path as an imbecile determined to make my life more miserable than it already was.

Yeah, yeah….I did my manly best to suck all this up and keep it indoors and I would like to think I was more or less successful. Whether I was or not, you will have to ask those few people who had to deal with me up close. But the truth, I know, is that the entire experience reduced me to something like a moderately intellectually disabled, immoderately immature teenager with an attention deficit disorder.

All of which has caused me to think about, as a contrast to the paradoxical usefulness of emotional suffering, the remarkable pointlessness, the uselessness, of physical pain. And the imperative to vanquish it, whenever and wherever it exists. It is one human condition that seems to lead nowhere, that points to nothing other than the most brute facts of existence—you are small and finite and at the mercy of nature—without offering something redeeming in return; or else the return is diminishing and not commensurate with the cost. Physical pain is universal—no one will escape it entirely—and it may be that what can be said for pain is that it reminds you what it is like not to be in pain. But, again, that presupposes a recovery, which may not necessarily be in the natural course of things and may be dependent on someone who cares enough (or is paid well enough) to help relieve you. And anyway, I don’t want to give too much ground on this, because the bargain (if that’s what it is) seems to me to be a swindle—you lose too much and become too diminished in the transaction. Hitchens dealt with this in one of his last pieces before his painful death from esophageal cancer, taking on that cliché about things that don’t kill you making you stronger. (Evidently, some things can make you weaker and then will kill you anyway.)

And on the side of recovery one has to credit the work-a-day diligence of those doctors and nurses and therapists whose job it is to vanquish pain. When I first visited my doctor four months ago with my initial, less severe, experience of this injury, this doctor—whom I have come to trust and revere—discussed various treatment options. Physical therapy was a given, but there were medicines, anti-inflammatories of varying potencies to consider, along with their possible side effects. At the time I recall that when I showed up at the office my symptoms had somewhat mysteriously subsided, so there was some legitimate question whether a prescription was necessary. And I recall that as he was reviewing my chart, and without quite looking at me, he wondered in a seemingly off-hand, and possibly whimsical way, if perhaps “a laying on of hands” would be enough. Whimsical though it may have been, I am quite sure he was in no way diminishing the severity of what I had experienced. Smart doctors, I think, know all about the “laying on of hands,” know all about patients who “mysteriously” get better when they get a little attention, a little assurance that they aren’t going to be killed by what they experience. Who has not felt better, a little bit anyway, entering the work-a-day hum of a doctor’s office and knowing suddenly that so much trained, perfected expertise cannot but prevail against some trifling symptom?

I did get a prescription, then, and took some physical therapy, but realize now I didn’t take it seriously enough. Which explains why I was back four months later. This time, I saw one of my doctor’s colleagues, a sharp, friendly young woman who intuited quickly how agonized I was, tried to amuse me with some humor, laughed readily at my own attempts to make light, wrote me a prescription for a short course of low-dose prednisone and some extended physical therapy, invited me to call at the drop of a hat, assured me that if some more specialized attention was necessary it would be ordered immediately, and sent me on my way. Once again, my kindest feelings about physical pain are all on the side of those who do what they can to get rid of it.

Two last thoughts: The pointlessness of physical pain, once you have experienced it yourself, seems to me to be the last word anyone should need on why not to inflict it on anyone else, including one’s worst enemies. What cause, short of the most immediate need for self-defence, is worth becoming that cartoon bully, the messenger that life is an empty shell?

And then this: some 15 years ago, I wrote a little bit in a professional way about advocacy, on the part of some physicians who specialize in pain management, for the legalized use of heroin in terminally ill patients for whom morphine isn’t enough. I believe its use has long been legal in the United Kingdom, but I am entirely unsure of its legal status in the United States and have long since lost track of this subject. Back then, the cause had a seemingly unlikely champion in William F. Buckley (seemingly, I say, because Buckley could be counted on to take on some esoteric subjects and adopt some surprising stances). In any case, he was for it and so am I. There is an argument against this, about the dignity of human beings in their last days, about the integrity of human suffering, and about how people ought perhaps not to be subject to treatments in death they would never consent to in less dire circumstances. It is a potent and valuable and substantive and elegant argument, and I say the hell with it. And I say: Vanquish the pain! Because the last thing anyone needs to be reminded of, particularly when they are dying, is about pointlessness.

No comments:

Post a Comment